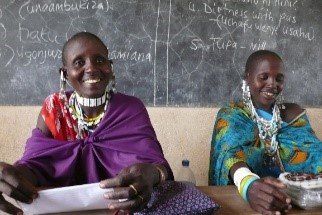

This idea of sharing – of integration – is crucial: ideas flow back and forth between partners. There is no sense of coercion, manipulation or hidden agendas. We work from the assumption that people will choose what is best for themselves and their families if they are given reliable information and provided access to reliable services. Their life experience deserves our respect – and allows us to be more responsive in why and how we teach.

When we began Natron Healthcare in 2008, the communities of Magadini and Wosiwosi asked us to teach them about Sexually Transmitted Diseases. We began looking for health education materials designed for Maasai people, an ethnically distinct, semi-nomadic group living predominantly in the semi-arid region of northern Tanzania and southern Kenya. We soon realized that all educational materials, particularly those designed for STDs and HIV/AIDS, depicted and were designed for Swahili or unspecified African people. There was also a dearth of information about sexual practices in Maasai culture that might explain the reason for and extent of STDs/AIDS prevalence. Without understanding why STDs were an issue for the community, we couldn’t teach simple solutions.

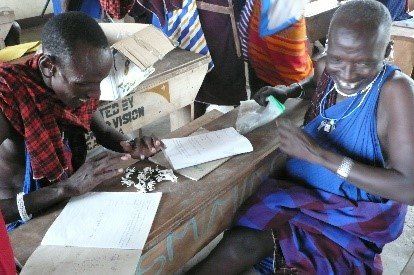

Penny contacted Andrew Knight, a healthcare educator and artist with extensive experience in rural Pakistan. She had worked with him previously in 1996 in creating STD/HIV education materials for Maasai in Serengeti using hand-drawn images of Maasai. Andrew hypothesized that use images

specifically of Maasai people would motivate discussion and the development of narratives by communities about relationships and practices that influence

sexual health. In 2010, Andrew created for NHC a series of images from everyday Maasai life such as people, livestock, huts, wild animals, etc.

Given Penny’s decades of experience as a GP and educator, we took an “open participation” approach: we sat in a communal circle asking questions aimed at generating discussions both within the workshop forum and informally afterwards – and at educating us. We kept our tone neutral or

empathic; we expressed genuine interest; we encouraged gentle humor. The communities – whose invitation and permission was crucial to obtain – viewed us as equals seeking to understand the issue from the inside, rather than judgmental outsiders attempting to impose a rigid, impractical or irrelevant solution.

At the communities’ request we then developed a “menu” of education modules for health issues such as anaemia, dehydration and immunizations. For the past 12 years we have used these with quantifiable success, seeing not only behavioral change in prevention and treatment, but in the desire for and confidence in primary care.